by Megan A. Fagge and Robert A. Just

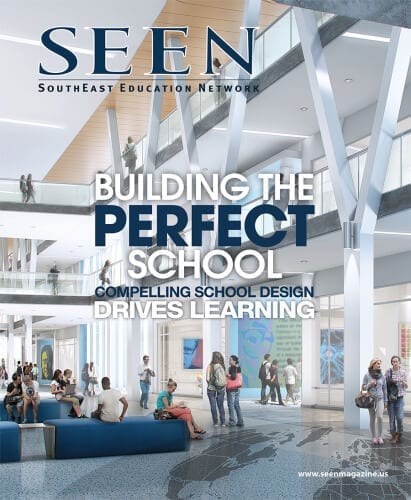

Children are impressionable and the experiences they have while in school will have a profound impact on their lives. Compelling school design can inspire children and their awareness of the built environment. Simply put, the perfect school will inspire, transform and bring added value to the educational systems and communities in which they operate.In today’s world, students are preparing for a technologically driven future with jobs that in many cases have yet to be invented.

So how do we create “The Perfect School” that not only enables students to excel, but also supports them as they prepare to join the global economy? In short, we believe the heart of this complex question resides in one single concept: Pride of Place. The perfect school should encourage students to learn and empower teachers to educate. As architects, we strive to create environments that connect people and places, making communities more valuable. From the start, the architect must engage interior designers, landscape architects, urban planners and graphic designers, as well as the educators, administrators and community. Collaboration, a cornerstone in 21st century learning, should also be the mark of great school design.

So how do we create “The Perfect School” that not only enables students to excel, but also supports them as they prepare to join the global economy? In short, we believe the heart of this complex question resides in one single concept: Pride of Place. The perfect school should encourage students to learn and empower teachers to educate. As architects, we strive to create environments that connect people and places, making communities more valuable. From the start, the architect must engage interior designers, landscape architects, urban planners and graphic designers, as well as the educators, administrators and community. Collaboration, a cornerstone in 21st century learning, should also be the mark of great school design.

We believe that when students take pride in their school, they learn to take pride in themselves and their community. As the success of a student is often derived from the support of parents and the community, Pride of Place extends beyond the student, to the community as a whole. The perfect school should encourage a student to say, “I go to school there” with a true sense of enthusiasm, and it should emphasize the value of education, collaborative learning and character development both inside and outside the classroom.

Design Matters

From a functional perspective, there are many components that would be at the top of any school administrator’s list when confronted with creating the perfect school. Such components often revolve around energy efficiency and general maintenance often described as High Performance Schools. Although these components are key and not to be overlooked, the design of the perfect school begs much more.

Intuitively, we know that design matters. Teachers have long compensated for dull environments by creating colorful bulletin boards and hanging posters. They have attempted to improve their space with area rugs and carefully placed bookshelves. Teachers know that design matters; however, all too often, they are not invited into the design process, which we see as a missed opportunity.

Our environments tell us who belongs, what behavior is expected, and what is valued. Recent research demonstrates that our students are  most certainly receiving these messages. At the University of Salford Manchester, data was collected from 751 students across a variety of learning environments. The results of the study were clear and compelling. The classroom environment, including lighting, spatial organization, even the color on the walls, “could affect [the students’] learning progress by as much as the average improvement across one year.” Subsequent research from the university has supported this initial conclusion — design in schools matters.

most certainly receiving these messages. At the University of Salford Manchester, data was collected from 751 students across a variety of learning environments. The results of the study were clear and compelling. The classroom environment, including lighting, spatial organization, even the color on the walls, “could affect [the students’] learning progress by as much as the average improvement across one year.” Subsequent research from the university has supported this initial conclusion — design in schools matters.

In a new study recently published in the Journal of Educational Psychology, and conducted by the Washington Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences at the University of Washington, the results were equally pointed. Female enrollment in Computer Science classes tripled when the classroom environment was redesigned. To quote the lead author Allison Master, “Our findings show that classroom design matters — it can transmit stereotypes to high school students about who belongs and who doesn’t in computer science.” This study is particularly intriguing because the classroom was redesigned based on psychological rather than functional concepts. The redesigned classroom space was to be “inviting,” not reflect gender stereotypes, induce a sense of belonging and communicate an expectation of success. Imagine the impact this could have across the field, if the results of this study were carefully considered in the design of our educational environments.

In addition to affecting students’ rates of learning and their sense of belonging and willingness to engage, the design of a school can affect the budget and bottom line. The San Francisco Unified School District was losing money in their school cafeterias. They had a large infrastructure dedicated to providing lunches, many to students entitled to free or reduced lunch, but were operating at a loss when students chose not to partake. The school district had been trying to address the quality of the food, the most obvious culprit, but the changes were making little impact. Usher in IDEO, a globally recognized design firm that took a fresh approach to examining the problem and realized they needed a “human-centered” solution. They recommended a communal, family-style dining experience for elementary students, while the experience was more varied for older students. The lunch hour, considered experientially through the eyes of the student yielded solutions that turned out to be mutually beneficial to the school system.

At Georgia Southern University Dining Commons, we created quieter spaces focused on study or respite as well as spaces geared more toward socializing at lunch. The spaces were designed to enhance the student dining experience.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the design of these environments is inherently impactful on student experience and learning. Each decision has an impact on our students whether intended or not. While there are many factors to consider in design, it is important to remember the mission of the building — not just to house but also to educate and nurture the development of children. It is with this focus that perfect schools are created.

COMPONENTS

Environmental Considerations

Reflecting on the studies above, there are a few key elements to consider in designing the perfect school. One feature to think about is lighting. The perfect school would include natural light and lots of it. As architects, we would accomplish this with floor to ceiling windows, skylights and atriums. Our design of the 11-story North Atlanta High School, which opened to students in fall 2014, incorporated floor to ceiling windows that let in plenty of natural light and offered inspiring view.

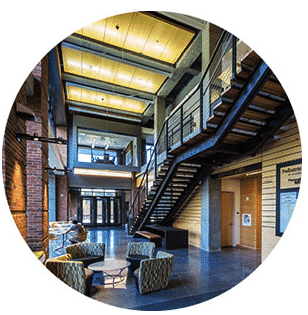

Another key design focus for the perfect school is spatial organization. It’s not just about proper adjacencies, but also how you connect the dots and create the paths in between that will encourage interaction and promote learning. Learning doesn’t just take place in the classroom. It also takes place in the corridor, cafeteria, playground and all the places in between. In designing Bailey’s Upper Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences, we integrated open spaces that allowed students to socialize and collaborate in between classes. The perfect school would have spaces of opportunity — a place outside the classroom where a teacher could sit with a student and explain homework or a spot for students to prepare for a class presentation. Learning can happen anywhere, and the perfect school would facilitate opportunities for learning and growing to occur around every corner.

In addition to spatial organization and lighting, color is a key consideration in designing the perfect school. We want to stimulate our students, not put them to sleep. This isn’t to say every color should be bright and bold as there is certainly a place for sophisticated and calming colors, but designers shouldn’t be afraid of color, particularly if it’s paint. With our design of Benning Elementary School, we incorporated bright colors and bold patterns throughout, energizing the students and faculty.

Integrating Proven Pedagogy

Extensive research and prominent educators say that education must shift from traditional lecture style instruction to discovery. Thus as a foundation to the education process, active-based learning has been growing in popularity. Variations of active-based learning include deeper learning, expeditionary learning and blended learning. These styles have much in common, promoting a student’s experience that, at its best, is investigative, personalized and engaged. Much has been written about this pedagogical approach and we certainly see this type of creative learning demonstrated at the university level. Stanford’s d.school, Harvard’s Innovation Lab, and MIT’s Media Lab all assert the idea that discovery through design and exploration fosters a type of learning that is not often supported by more traditional educational environments. And it’s catching on in the K-12 classrooms.

This active-learning approach provides an environment poised to foster the performance characteristics of curiosity, teamwork and perseverance all of which correlate to success. Embedded in a child’s education, these characteristics prepare students to love learning and become engaged in the process. And with retention rates tied directly to the style of teaching and learning, active-based learning strategies have become important components in the design of educational environments.

Active-based and personalized, student-center learning requires a new conception of classroom organization that is both flexible and agile. In the perfect school we move away from traditional desks in rows and begin to look for space that is flexible, adaptable and configurable to a variety of activities and experiences as the curriculum requires. Such space can and should be designed to foster learning. This isn’t to say that we should toss out the traditional classroom in its entirety; rather, the traditional direct-instruction classroom organization becomes one setup in a variety of spaces that can be utilized by staff and students. These setups include team collaboration, individual study, project based learning, distance learning, traditional passive learning and learning though presentation. In this scenario, the ability to change the environment as needed to best suit the process of learning, and moreover the ability to do it quickly and with little effort is critical to 21st century learning.

The concept of “learning on display” should also be incorporated as a way to encourage and support interaction and collaboration. Teacher collaboration, student collaboration and active media center concepts are all about putting ideas together, creating positive school climates, pushing the boundaries of technology integration and fostering connections to the environment, community and global network.

collaboration, student collaboration and active media center concepts are all about putting ideas together, creating positive school climates, pushing the boundaries of technology integration and fostering connections to the environment, community and global network.

Learning on display is a vital part of 21st century learning, and can be achieved by designing learning spaces to be open and transparent. For example, at Emory University’s Atwood Chemistry Hall, we incorporated glass walls for science and research labs to inspire and encourage students to create and experiment.

As well, educators understand that the education process takes place beyond the classroom. It happens on the Internet and playground, as well as the hallways and cafeteria. Invariably these spaces become key components in the educational process and deserve special consideration when designing facilities consistent with innovative learning opportunities.

One school that has harnessed this concept is Georgia Tech with its new Engineered Biosystems Building. Few projects could be a better example with its transparent interiors that enable students and staff passing through the building to see into labs, study spaces and classrooms. The transparent design is intended to create intrigue and encourage the cross pollination of ideas that will inspire students to collaborate and think outside of the box. Even the lobby of this new facility has an interactive monitor that literally puts learning on display.

Technology-driven design is another key component to creating the perfect school. Many schools are experimenting with “flipped classrooms” or “blended learning” where technology is leveraged to deliver some portion of the content freeing class-time and teachers to engage in more personalized learning exercises or pursue deeper investigations of the material. Clintondale High School in Michigan experimented with the flipped classroom, and noted dramatic reductions in failure rates across academic disciplines as well as a reduction in disciplinary problems. The results were so compelling they have committed their entire school to the model.

Another school garnering quite a bit of attention is AltSchool founded by Max Ventilla, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur. The school is focused on personalized learning experiences, and has been referred to by its founder as Montessori 2.0. Technology rich, these one-room schoolhouses of the 21st century are attempting to re-invent education by creating environments where students can follow individualized and self-paced curricula anchored by technology. At the forefront of technological integration in schools, AltSchool has even invested in a product, engineering and design team office within the school itself to design, among other things, hardware and software applications to further optimize the pedagogy.

As we noted in the beginning, the success of the student is often derived from the support of the parents and community. With that understanding, we believe the perfect school works with the community. We don’t just mean providing space for intramural sports and voting precincts. We mean true collaboration with the community in forming partnerships with local organizations and private companies. As an example, we are working with one local Atlanta school district to find ways in which the school district can collaborate with private sector organizations. This might include collaboration with a network of local hospitals in short supply of specific professions such as EMTs and nurses. We suggest the perfect school might collaborate with such organizations where there can be shared spaces that will enable the organization to come in and coordinate programs that will intrigue young students to consider professions they may not have previously considered.

Conclusion

When considering what it takes to design the Perfect School, we certainly want administrators to value recent concepts that embody “High Performance” schools, but we also want to encourage administrators to embrace the pedagogy of 21st century learning. Putting it all together in a collaborative approach, the architect and administrator can create something great, something that creates Pride of Place and thus the perfect school.

Authors

Megan A. Fagge is a certified school teacher and architectural designer at Cooper Carry’s K-12 Specialty Practice Studio. Robert A. Just is principal and director of Cooper Carry’s K-12 Education Studio.

Original article, Designing the Perfect School, appeared in SEEN Magazine. Check out more thought leadership profiles in the latest edition of SEEN Magazine!